[

space

]

Preamble

I had never heard of Cubesats until one hopeful/fateful day in 2019 when the Dean of my (then) college sent out an email to faculty and staff about research project ideas that he would support during the upcoming funding cycle. (I think he was trying to inspire faculty to think bigger than how he perceived we were used to thinking and to make the institution a hub for “big R” research.) He had recently left the West Coast for Maine and was friends with a retired Berkeley scientist who offered to provide mentorship on the development of a small satellite platform about 40% larger than a Rubik’s Cube. Having had such a memorable experience working at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and loving all things space, I promptly replied to the Dean’s call and expressed interest in working on such a project.

I had just finished my third book on energy (energy efficiency, this time around) and was primed to start a new project on air quality monitoring. I had gotten some seed funding and had just co-located some Purple Air sensors with the state’s regulation-grade sensors in Portland. But, the siren call of doing spacecraft development was great enough to distract me from the more realistic endeavor I had set out to do.

The first red flag I should have paid attention to was that the Dean would be the principal investigator (PI) and I would be a co-investigator (Co-I). Deans are too busy to do anything more than their typical duties, which seems to entail, among other things, going to and convening a lot of meetings and keeping provosts and department chairs happy enough. And as a grant proposal reviewer, I know that unless the project is curriculum related it is looked at poorly to have a Dean lead any type of investigation, let alone a science one. Of course, it did not take long for him to offer me the “amazing opportunity” for me to be the PI on the project and submit it to NASA’s EPSCoR Research program. So there it was, I was now the PI and began the task of getting a proposal together with very little help and no other faculty member intertested in the project (at least at that time). The thought that this project in its first iteration could compete with the flagship research university’s proposal submission is now laughable to me, but our “Earthshine” CubeSat proposal was a scientifically interesting and technically plausible project and I really do think that if it could be completed, would result in some pretty cool science. That submission did not make it out of the state competition but I will give credit to the Dean – his persistence on getting seed funding from the state space grant agency resulted in a good chunk of money headed my way to try to make a solid prototype system.

All of this preamble is here to say that once the seed money came in, I immediately felt that “oh crap” moment that a researcher feels when they realize they are actually going to have to deliver a product within a certain time. And, by starting from scratch, I had to do a lot of reading on what Cubesats are, how they work, how you get them into orbit, how you uplink/downlink (i.e. communicate) with them, and most importantly what kind of team is actually needed to realistically complete such a project. As the project manager, I had to be able to properly communicate to interested individuals the cool factor of the project and why they should work on it. After a lot of reading, I came up with a presentation on Cubesats that forms the basis of this post.

Starting with helpful sources

I love getting into the weeds of a good literature review. So if you want to get into the CubeSat world, I’d recommend using the following resources, which informed my Getting Started with CubeSats presentation (these are external links, I receive no compensation for sharing them):

-

Sandy Antunes’s DIY Satelite Platforms is an excellent introductory text on small satellites, including Cubesats. It’s a bit out of date and it’s more a personal diary of Antunes’s hobby satellite project, but it was an essential launching point for me. It was worth the $5 to have it on my kindle.

-

Andrew Barron’s Amsats and Hamsats is, best I can tell, a self-published primer on how to communicate through amateur radio satellites (AMSATS, also the name of the Radio Amateur Satellite Corporation). You need to know things about Ham Radio and Software Defined Radio to really appreciate the book, but that knowledge also is a baseline need for completing a successful CubeSat project. Absent that, having a licensed amateur radio person (a Ham) on board with your project is a pre-requisite to working with satellites. Don’t discount this book because it was self-published, it is a great source of information.

-

NASA’s Cubesat 101: Basic Concepts and Processes for

First-Time CubeSat Developers is another free and essential document to use when starting a serious CubeSat project. CubeSat 101 was produced under contract by the Cal Poly CubeSat Systems Engineer Lab and supported by the NASA CubeSat Launch Initiative – Cal Poly co-pioneered the CubeSat platform. This document does not disappoint (though it was last updated in 2017, so it may be time to revise it!). CubeSat 101 covers development, mission models, requirements, licensing, and certification. As soon as I read this document, I knew it would be a steep uphill climb to achieve success, but the journey might just be worth it.

I’ll share some more useful references at the end of this post but these are the three I used first, for better or worse.

What are CubeSats?

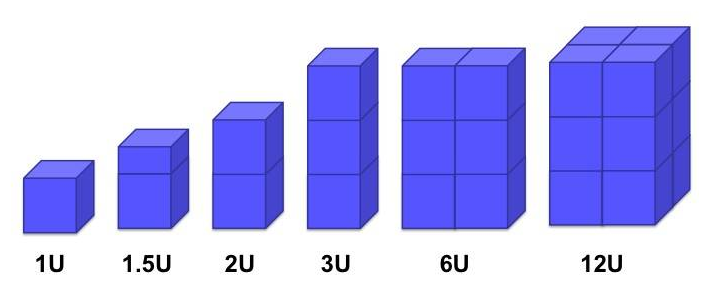

CubeSats fit into a class of small satellites called nanosatellites, ranging from one to 10 kilograms in mass. However, the distinguishing dimension of a CubeSat is volume – CubeSats use a standard size and form factor, measured in units. A “one unit” or “1U” measures 10 cm x 10 cm x 10 cm. So, basically a cube that is a little bigger than the aforementioned Rubik’s Cube. CubeSats are extendable to larger sizes though: 1.5, 2, 3, 6, and even 12U or 24U. See the figure below for a very simplistic depiction of the sizing. (Image source: NASA)

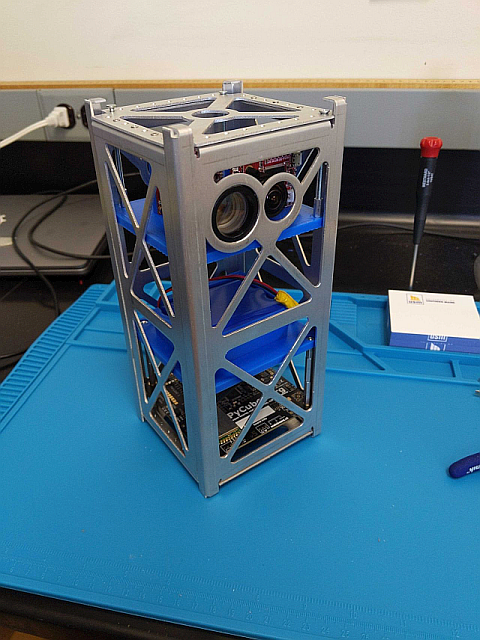

For reference, this is a physical example of my Earthshine 2U proof of concept prototype. Shout out undergrad David Breen for the design work on this. Notice that this 2U isn’t two 1Us attached to each other, but rather a full frame 10 x 10 x 20 cubic centimeters in volume. I’m not sure if we’ll ever get past this stage, so I figure I might as well milk using this photo. (If anyone is interested in continuing the work, please let me know!)

Showing this picture also helps solidify the point that a CubeSat is a specification (or “spec”), not off-the-shelf hardware. You are the developer and can design your own frame specification and then pack in whatever you want as long as it fits into the 10 x 10 x 10 cube, or some multiple. Once a CubeSat is designed, constructed, tested, licensed, and launched, CubeSats are released into orbit from CubeSat deployers, sometimes directly from the ISS, other times from a small vessel that gets launched from the ISS. (Image source: NASA)

Fun Fact: Bob Twiggs, an originator of the CubeSat idea, challenged students from the original CalPoly and Stanford team to make a satellite the size of a Beanie Baby display case. I’ve confirmed with James Cutler (UMichigan) and Michael Swarthout (St. Louis University) that this is a true story, but the form factor was a bit too small so they settled on the 10 cubic centimeter standard. It was more of an engineering challenge and for hands on learning than to be used for doing science, at least at first.

mass specification and comparison

Recall, CubeSats fall into the class of nanosatellites ranging in mass from 1 kg – 10 kg, but CubeSats typically are not greater than 3 kg (most missions are about 1U to 3U). For reference, a large satellite like GOES-R, has a dry mass of 2800 kg and when fueled, is over 5000 kg (> 11 000 lbs!!!) and it’s largest dimension is 6.1 meters (20 ft).

core components

CubeSats, or any kind of nanosatellite, tend to have these common core components:

- An antenna

- A radio transmitter for uplinking commands and/or downloading your data

- A computer-on-a-chip (think Arduino, Raspberry Pi, Custom, etc..)

- A power system, most often solar cells plus a battery plus a power bus

- Sensors/Instruments for collecting data

These components are very similar to what you would find in an IOT (internet of things) device. That’s the educational value of initiating a CubeSat project at schools – it provides an entry point to space technology and simple science at a potentially very low economic cost, on the order of thousands to tens of thousands of dollars, with launch costs around $50,000 - $100,000 per 1U. Launch companies are sprouting recently and it is expected that the price to launch will come down some.

Of course, the more ambitious your research goal and/or project mission, the more it will cost to complete it. Once you form a proper team of researchers, staff, graduate students and undergrads, you can easily top $1 million for the budget of a very simple university CubeSat project. That mostly comes from having to pay people money to work, which can be a foreign concept in Academia. If you want to do cutting edge science and engineering, the budget climbs into the $2 - $10 million dollar range for a 2U to 6U CubeSat project. That’s top notch R1 money or a modest NASA budget. Keep in mind that large satellites can cost $100 million to $1 billion, so even at $10 million, that budget is cheap. That’s why CubeSats are viewed as an opportunity to democratize space and from NASA’s perspective, a cost-effective fail fast fail cheap strategy.

eye candy: the MarCO mission

I can point you to a number of simple but exciting 1U – 3U missions, but why not introduce you to a crowning achievement? I had the amazing fortune of attending a web presentation by Andrew Klesch, the chief engineer for NASA’s super ambitious and altogether awesome Mars Cube One (MarCO) Mission, which were twin communications-relay CubeSats, built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The mission was for these CubeSats to fly by Mars in support of the InSight lander’s entry-descent-and-landing activities.

Check out this animated explainer:

And this engineer profile:

That was awesome, right? The MarCO mission was a prime example of the seemingly infinite potential of CubeSats and related technology. Realistically though, most CubeSat missions will be set to do some kind of science and or technology demonstration in low earth orbit and likely will be an Earth-pointing, Earth-observation mission. People often forget that the majority of satellite missions are to learn more about the only planet we know for sure contains life.

other points

Other key points to keep in mind about CubeSat projects are: 1) CubeSat projects often involve engineering, assembly, and integration and 2) Launching a CubeSat is the “easiest” part because you don’t do it (you pay someone else to), but it’s probably the most expensive especially for 1U college or amateur projects. As you’ll find in the CubeSat 101 resource, you can apply to have your CubeSat added to a scheduled NASA and/or ISS manifest for a free ride, with considerable strings attached, of course.

The CubeSat Mission

Once you have a basic working understanding of the components of a CubeSat, you can start thinking about developing a mission and then looking for the components and people needed to carry it out. Keep in mind the following points, mantra if you will, when deciding to pursue a Cubesat project:

- Have a clearly defined mission

- Find the right team members to accomplish the mission

- Get funding and all of the proper licenses

- Hope for a successful launch

- Do everything under your control to achieve a clean radio signal

- Pray for a long enough life to achieve the mission goals

- If 4 – 6 fail, claim success anyway by saying you learned a lot (haha)

mission goals

Given these parameters, what mission goals are you going to tackle? What do you want the CubeSat to do? To help answer these questions, consider breaking down possible options into 3 main categories:

- Science Mission - measure stuff

- Engineering Mission - test hardware or software

- Amateur Missions - low and high concepts, anything you can think of and get funding for

science missions

On a science mission, your CubeSat will measure something. Two main types are:

- pointing

- in-situ

A pointing mission would be like using a telescope with a camera sensor. Your CubeSat points at any object of interest (the Sun, Earth, the Moon, other stars, etc.) and makes observations. In this case you can’t point randomly if the mission is very specific. Active pointing is very challenging on a CubeSat, requiring magnetic torquing or reaction wheels for precision control. That gets expensive so you have to play tricks like using a large field of view lens on your camera essentially to create a survey where you can make sweeps across a plane in a predictable fashion and discard bad observations. It’s still challenging but not as challenging as precision pointing.

A good case study on high-precision pointing on a CubeSat can be found here

In-situ missions are much easier to complete – you use sensors that take measurements of a region without the pointing requirement. So, measurements like temperature, electric and magnetic fields, light from the sun, tracking orbital position, and similar measurements are very much in reach.

engineering missions

On an engineering mission, you can use the CubeSat platform to do component testing. For example, you can test out new hardware and measure how it performs and assess its viability as a next generation spacecraft replacement. You can also test next generation hardware or software improvements for power systems and management, positioning methods, radio communications, etc. Another area of interest lies in small-scale testing of new propulsion systems such as solar sails. The MarCO mission was considered an engineering test mission, for example, because of the antenna array that was designed to complete the mission. The New Moon Explorer (NME) robotic mission concept would be another. Shout out to my former NASA supervisor Joe Nuth for letting me know about this cool project.

amateur missions

On an amateur mission, you can use the CubeSat platform to do a lot of cool projects and you don’t typically have to worry about mission length, since the value mostly lies in the exercise of constructing, testing, launching, and talking to the satellite. Typically, “hams” use CubeSats to communicate with other “hams” using satellites built with transponders or repeaters on amateur radio frequencies. Many early amateur CubeSat projects were designed only to send a repeating message for ham’s to receive and track. Similarly, many projects gather some simple in-situ measurement and transmit to Earth for ham’s to receive. Most often, amateurs are recruited by university teams to work on science-oriented missions and offer valuable expertise in ground station design and satellite communication. Actually, the amateur community is an irreplaceable resource for ground station communication for satellite operations. See SatNOGS as a shining example.

commercial missions

It is worth adding that there is a growing commercial presence in the CubeSat world. Several companies are using the small satellite platform to provide telecommunication services and for capturing Earth observation imagery. High resolution imagery is valuable to clients in agriculture, city planning, and military to name a few. Planet labs is a good example of the use of CubeSats for commercial applications.

Where will your CubeSat go?

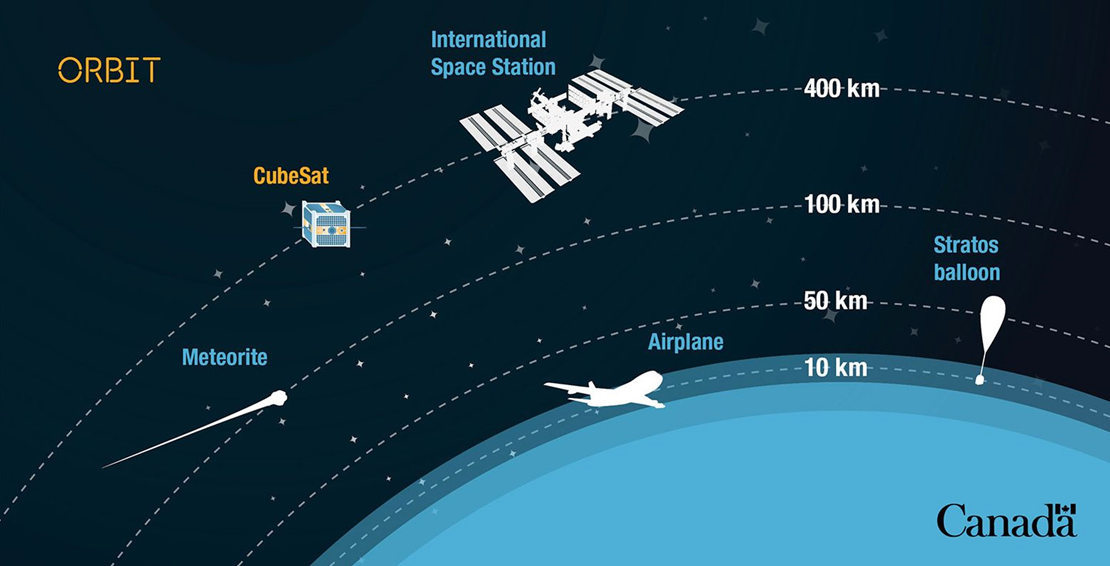

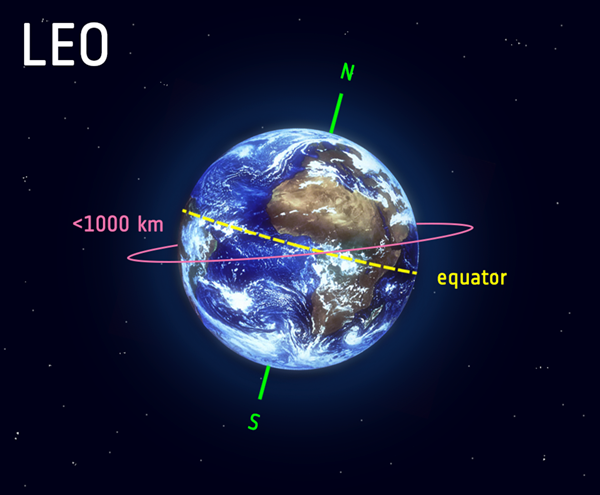

Part of mission planning involves placement of the satellite in orbit around Earth. The mission can be limited by your ability to secure a certain altitude and vice versa. Most often your CubeSat will go to Low Earth Orbit (LEO), in a broad band ranging from about 150 km to 600 km (93 miles - 370 miles). This region coincides with much of the ionosphere and Earth’s magnetic field. This is where most satellites and the ISS reside because it shields objects from the fiercest aspects of the Sun. (See cartoon below depicting relative locations of objects in the lower atmosphere courtesy of the CSA) LEO is about as safe as space can get for a CubeSat.

A typical LEO has about a 90 minute period, it revolves around Earth once every 90 minutes, doing about 15 orbits per day. Orbits can be nearly circular or highly elliptical, coming closer to Earth at one end of the orbit and then moving far away at the other. Also, CubeSat orbits can be positioned near Earth’s equator (equatorial orbits) or loop from the North to South Poles (polar orbits).

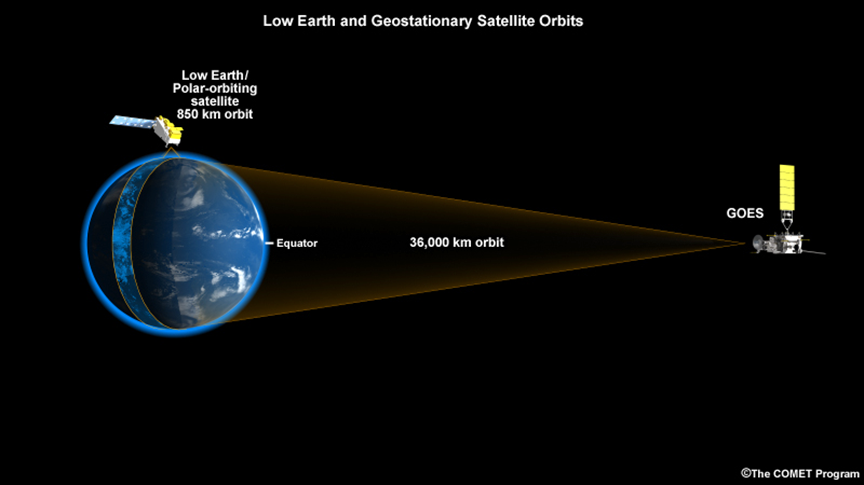

Larger satellites can also be positioned in Geostationary orbits, moving at the same speed as Earth so they can take the same measurement over the same field of view continuously. Think back to the GOES satellites.

Geostationary satellites have been a tremendous asset to our ability to track weather and aerosol movements from space. The information collected from these satellites has applications in agriculture, drought management, air pollution policy, among many others.

orbit height determines mission length

When planning your mission it is important to keep in mind that the higher the orbit, the longer your spacecraft will last. At 250 km, because of drag on the spacecraft, a CubeSat will live between 3 to 16 weeks before it re-enters and burns up.

Missing Bits: Licensing and Assembling a Team

I think I covered much of the basic points that would get you started down a CubeSat rabbit hole, but two key points that also need to be considered are: how to assemble your team and what you have to do do get the proper licenses from Federal entities.

On the team assembly side of things, I quickly realized that you need a core team of about five people that will make a full investment in the project. You need someone able to design and fabricate prototype parts. You need someone that knows radio and communications, to help design a ground station and to navigate radio testing. They also need to be a licensed ham. You need someone willing to go through the details of the payload and help hash out the science and design of the sensors to accomplish the science. You need someone who knows their way around electronics. You need someone who knows how to code. All of these people really need to be invested. Then you need a cadre of students willing and able to carry out all of the details that are set out by the core group of experts. If I’m recalling correctly, Andrew Klesch said MarCO required about 17 engineers to successfully complete the project and that’s with a lot of experience already had. That’s why a newbie institution should look to collaborate with a veteran or set out to do a very simple “beep-sat” – something that does the bare minimum but likely will work. Even then, the CubeSat failure rate is exceedingly high for university CubeSat projects. I’ve had some exchanges with Michael Swarthout, a professor at St. Louis University, and he keeps a census of CubeSat projects. You can go to his website here, but most projects fail with a success rate around 30% last I checked.

Finally, I’m not going to comment much on the licensing side of things other than you will have to look at NOAA and FCC rules on CubeSats. If your mission involves a camera, you’ll have to check both agencies to see if you need a license. If no camera, then you likely will only have to deal with the FCC. You’ll need to report all of the details about your mission, especially the communications system. It’s not impossible, but it can be arduous. I didn’t get far enough in the Earthshine project to get to the FCC but an over eager former student filled out the NOAA licensing form for me on my behalf and they made me talk to about five representatives on a Zoom call to give them a run down of what we planned to do. It was a little nerve racking for sure.

Concluding Thoughts

Building a CubeSat for demonstration/simulation purposes is an amazing experience and really beneficial to understand spacecraft design, hardware, and software. But don’t try to build one for an actual orbital science mission unless you have the team, infrastructure, financial and managerial support, and patience needed to complete such a daunting project. Even then, you are at the mercy of the hardware surviving launch and orbital deployment. Also, expect to get frustrated by others not being as enthusiastic about your pet project as you are. Finally, if you are doing this at a university, you really need long term support and buy-in. This realistically is a 3-5 year project for beginning organizations before you even launch it. Make sure to get administration to provide you with the financial and temporal support needed to get it done.

Unfortunately for me, the Earthshine project I set out on was not completed and its future is in question, the result of a number of unforeseeable factors, not the least of which was the Covid-19 pandemic. If given a legitimate shot, I still think it can be done, but it would have to be done at a true research university, where the physical and human infrastructure is in place to carry out the, at times, herculean tasks of building a tiny spacecraft that could survive a launch, begin its mission, and successfully downlink its data for analysis.

Finally, I’d be remiss not to talk about Space Junk. Go to this LeoLabs Site to see all of the stuff in Low Earth Orbit. CubeSats can contribute in a meaningful way to democratizing space for education, science, and commerce, but they can also contribute to the growing problem of orbital debris in the upper atmosphere. Moriba Jah has been championing the cause around Space Debris and its impact on our planet. We are creating a lot of junk that is just floating around in the sky, which not only affects our view, but also can reak havoc on our modern communication systems. The skies are becoming like our oceans – at some point we need to consider things we launch into space as polluting Earth’s environment. Most enitites that operate in the CubeSat arena say that anything lower than 400 km will burn up in the atmosphere, however, there are not strict regulations on launch companies, so many satellites end up above this threshold almost guaranteeing objects will orbit the Earth for 25+ plus years and long after the CubeSat mission has been completed. We need to seriously review our orbital policy.

Additional References

Here’s a smattering of other links that could be useful: